What do you stand for? Who are you? How can you know that—and operate from that position of power?

There are times that it’s hard to know what to say. Things seem to ask for a response, even just a raised hand to say “Here”. But how to start with this world?

This week I discovered that the place where I work has a new brand tagline, and this is it:

Stands For Purpose

(It’s not that bad. My daughter’s primary school has Strive to Excel. Although this one’s apparently on the back of buses, which is about as funny as it gets.)

While I was still trying to figure out my own misgivings, let alone whether it’s legitimate to express them publicly (because brand) I came across a widely shared clip of bell hooks explaining how as a feminist she doesn’t find herself able to support Hillary Clinton’s run for President. In this one minute explainer, drawing down the powerful words of James Baldwin, she nails it for me: there are these identities we’re meant to embody with force and conviction, and yet they may not in any given situation represent the values that we stand for.

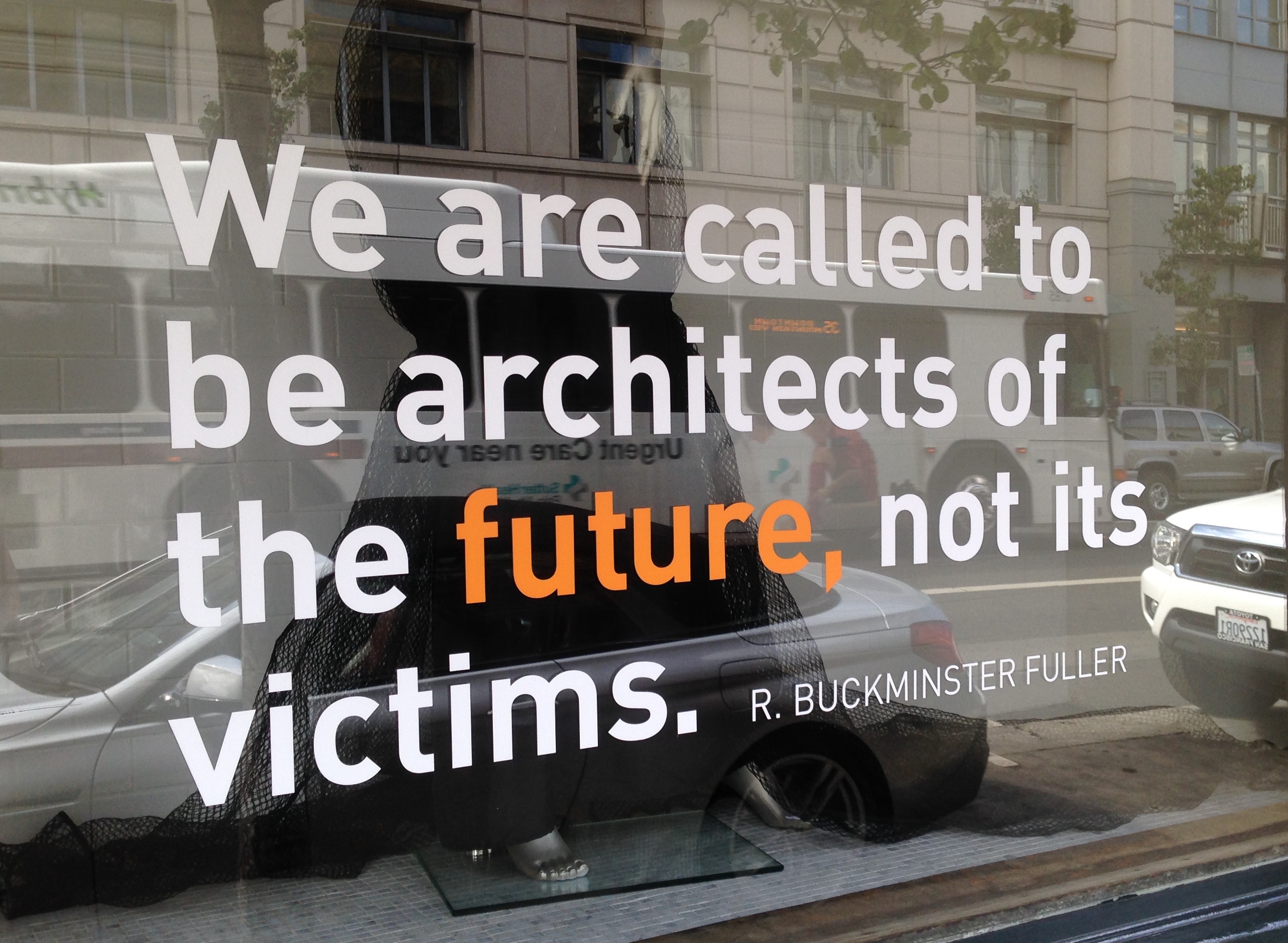

Values aren’t corporate mission statements or brand collateral because they’re personal. I suspect this is even true of people with faith, which I’m not. Values aren’t practices of compliance with institutional rhetoric, they can’t be. Values are who we are, and the only reliable source of our power to act in this world because they’re earned, through difficult experiences that make us proud of ourselves. Values separate us from machines and the stars. Our values make it possible to operate with intent, to think independently, to settle for ourselves the big question of how to live, what counts as enough.

So while I respect that this standing for purpose is the mission of my institution, and that it’s standing room only all the way to our chosen destination in the world university rankings, something else is tugging at me, something closer to what I’m learning that I stand for.

At the end of last year, I was asked a big question by someone whose thoughts are really precious to me. Are things getting worse, do you think? he said. And it’s complicated. The mood swings towards pessimism. Will children exposed to television ever play in cornfields again? Will the economy ever pick up? Will the planet survive our occupation of it? And because hard times have come again before, no one wants to get caught naively thinking things are different now. So we muffle our disquiet, because we’re not sure if our moment in history is a landmark or a decisive moment, or just another weary day.

But I think he’s really asking something about us, not just about what’s happening: are we the crowd applauding, whistling, cheering as the ice bridge caves in to the sea?

For me, the question is about work. Is it getting worse, and are we at risk of applauding as it does so, because we’re so busy standing for the spectacular, when we should be sitting and thinking very carefully about what it tells us about environmental cause and consequence?

I take this to be a question about employment as a whole, but the case study I understand best is employment in higher education. And because our role is to educate, it really matters how we manage our own working. Whatever we speculate in marketing or curriculum about the future of work, the practice we model to students everyday is how we occupy our own jobs now. Every time we meet, students learn from us how we sustain a critical professional voice as we go about our careers—and how we do this constructively, pragmatically and optimistically.

So let’s do this openly, and see what happens.

This week Liz Morrish has written an extraordinary post about breaking the code of silence in conversations with students about academic stress, and what systematic and structural pressures are troubling the people teaching them. She told them the story of Professor Stefan Grimm, who committed suicide in December 2014, and left clear advice for his professional colleagues about the particular workplace pressures that took him to that point. Several of us committed to keeping his name in our thoughts and our writing, and we have done so. But surely we shouldn’t talk about these things with students?

And yet, here’s what happened:

I hope I got it right. It felt as if I did. This was not a monologue; students had questions and comments. Most of all they offered support; their responses were simply heartwarming in contrast to the totalising judgement of management by metrics. As I lost my ability to contain my sadness, my voice trembled and I became tearful. A young woman stepped forward and offered a hug. Later more students arrived at my office with coffee and cake, or just concern. Students I barely know out of class offered more humanity and understanding than institutions with a duty of care to prevent workplace stress. I was humbled and grateful.

Two more writers have since responded. The peerless Plashing Vole detailed his 13 hour working day (and playlist, if you need one). And Siobhan O’Dwyer mapped out very carefully why even job security and a genuine appreciation of career privilege doesn’t remove the sense of personal unsafety that so often accompanies academic work.

Both Siobhan and Liz make clear that what prompts them to speak is the worsening health—and mental health—of colleagues. And this is also haunting me at the moment, for a whole range of reasons, not least the story of Fergus McInnes. In September 2014, he disappeared, and has not been found. His family are still waiting for some sense of what happened to him. With care and caution, his story was shared recently on the Matters Mathematical blog, and I found myself reading through his spare and beautifully written website, Fergus’s Brain Online. It’s just a big page of links like it’s 1996, but this is the story of a real human who was a colleague of all of ours, who carefully explained his struggles with depression, and his search for a way to manage it better. He had a stellar academic career.

What is a university’s responsibility if someone takes up an academic position and also has a disability of some kind, especially a mental health condition? Let’s make this simple: surely we should all be standing together for a safe mental health culture for everyone at work, just as there are wheelchair ramps into every building? If the expectations of academic pace and productivity are making work unsafe for some, shouldn’t we look harder at the values of the institution that causes these pressures to seem reasonable to anyone? Anyone?

Or have we really created a culture where, as I learned this week, a research executive who was told the story of Stefan Grimm responded that someone who enters a university career should understand what it takes to succeed. Is this how we persuade academics that it’s normal to push themselves beyond their own limits, without hope of care in return? (And is this relentless commitment to productivity at all costs the reason that academic job applicants who disclose hidden disabilities don’t get jobs?)

These are the values of an aspirational, purposeful economy in which everyone from students to whole institutions is lined up by rank, and the logic of measurement is used to allow the weakest performers simply to fail. It’s a brutal culture in which the competitive lucky ones get careers, and the rest get uberised or not employed at all.

Let’s stop standing for this.

Thanks to many influences here: Liz Morrish, Aidan Byrne, Siobhan O’Dwyer, Will Littlefield, Andy Clarke, Melonie Fullick, Mark Drechsler, Richard Hall, and the students and colleagues I get to sit down with every day.

7 Responses

This is a great post Kate, dealing with a very difficult subject. Of course, we shouldn’t shield students from the stresses and experiences of academic life but we need to be very very careful about how we do it. We know so little about the whole lives of people we work with, colleagues and students. On several occasions students have shared with me painful details of their lives that showed me how little I understood what they were experiencing. We do have a responsibility to take care of ourselves and our colleagues but I think of our caring responsibility for students as, I don’t know, even more important or at least qualitatively different. I remember a mature student whom I taught getting a job as a lecturer. She was someone who had many problems in her life and we all did our best to support her. When she joined the staff, she had the office next to mine and I would listen to the voices (but couldn’t hear the words) when she had student consultations in her office. What struck me was that she was doing most of the talking and I wondered if she hadn’t made that switch of roles. Of course her own experiences were part of her identity and important to her authentic engagement with them but what about balance? Telling our own stories is important but cacophony can interfere with listening

I think this is a key point, Frances. In any conversation, our sense of the importance of full disclosure can amount to talking at people, not listening to where they are in their lives.

Listening to students I feel continually ashamed that we recognise so little about the complexities of working life for them. Mostly, we still take a penalising approach to this, without actually asking why they work, who they work for, what value this work has for them.

But I’m not sure that I think we have a higher need to care for students than we do for ourselves or each other. If we advocate together for high standards of safety (especially in mental health) in the spaces that we work in together, then we begin somewhat on shared ground.

Writing this piece made me realise how much we pass on our own pressures to students, and again I think you’re right that this is about listening.

Thank you so much for reading and commenting.

As usual Kate, you cut to the core of the issue here, articulately and carefully. While I sometimes wonder if academics’ obsession with their unhappy working lives is a factor of most of them not having worked anywhere else, I pretty much agree. I recently completed my annual career review, and tendered letters from my counsellor and GP to account for ‘impacts on my productivity’. For the clinical psychologist’s letter, I asked her to delete a particular sentence because I worried that providing that information to my employer could take things out of my hands ( ie they may consider they had a ‘duty’ to report my sometimes precarious mental health to other authorities).

But re the point of your post, it has been those we label students who have been unquestionably the most supportive when I have made my difficulties public. They have done it in humbling, honest, beautiful ways. In my current space, I have found that it is repeatedly with students that I can engage over questions of ethics, morality, values. Raising these issues with most of my colleagues, I am met with a discomfited silence. I have just been discussing the culture of our school and research centre with their leaders, suggesting we build a culture of generosity and respect (as opposed to competition and secrecy) – it will be interesting to see the outcome.

Thanks for the insights, and carefully teasing out the threads of this issue.

Michael, thank you so much for bringing this story here. I have also found that when I’ve carefully and calmly disclosed health issues with students their responses have been exactly as you describe.

My aim when health issues are disclosed to me is to meet this standard that students themselves have set: to respond first with kindness, and second with what-must-be-done. So like you I find the space of teaching and learning to be filled with values that aren’t quite the aspirational ones currently labelling the tin, but are the ones that we all need to make work and life sustainable.

I am so interested to hear more about your proposal for creating a workplace culture of generosity and respect, and that you see these as the opposite terms for competition and secrecy. We are hearing so much about “competitive” as a goal, that to counterpose “generous” is a very powerful move. The opposing of respect and secrecy is even more complex.

Thanks Kate, I think that the tag line ‘stands with purpose’ might be fine except that it really means ‘stands for what the top of the institution think is important’ rather than the multiple purposes of staff and students. Perhaps the conversation that leads to a more supportive institution will include a deep discussion of the many different purposes required to keep the reputation strong in places other than the ranking gangs. The values of the classroom discussed above are not the values that lead to total ranking stardom, but rather the human values that promote learning and growth.

On goals and slogans – years ago at my daughters’ primary school, at the end of the school song that supported risk and daring, everyone shouted ‘Fly Be Free!’ Hardly any standing there.

[…] students, become more than moments of solidarity? How do they become movements of solidarity? As Kate Bowles argues academic narratives are […]

[…] K. (2016, March 13). Standing room only. [blog […]